UNIKA BALLS: THE SUPPLEMENT THAT COMBINES FUN AND WELL-BEING

If you have ever walked through the stables or along…

Feed and products in 25kg bags excluded

Bank transfer | Paypal | Credit cards

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

There is perhaps no animal that has played such a leading role in the imagery displayed in art as the horse. And who can better understand the reason for this than Unika ? That’s why today, we’re going to retrace some of the routes taken by the horse over centuries of the History of Art not just to look into the past, but to get to know our beloved horses better and look to the future with a little more pride.

Cavallo, 16.000/14.000 a. C. – Ocra rossa, carboncino e graffiti su calcare – Grotta di Lascaux, Dordogna, Francia

The depiction of the horse in art is deeply rooted in the imagination of human civilisation, which means that it was present in activities and life in general from the very beginning, as already shown in the prehistoric vase and wall paintings, such as those in the Lascaux Cave in France: around 15,000 – 10,000 years ago. Therefore, man had entrusted a key role to the wild animal.

The first detailed and precise anatomical depictions belong to classical artistic iconography. The Phoenicians and the Egyptians had already made the horse a fundamental means of transport, but it was in Greece that the horse acquired considerable importance, not only for warfare but also for the consideration given to the animal in the polis (the city-state), in the social and everyday spheres. And it is in Greece that its depiction, particularly in the so-called ‘black-figure amphorae’ from the Attic period, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, took shape as an expression of sinuous forms, a translation characterised by silhouettes with robust bodies and long legs.

After all, we cannot forget the role entrusted to the steed in epic literature: the legendary stratagem of the Trojan Horse, an ingenious expedient used by the Greeks to penetrate the city of Troy in the fateful battle narrated by Virgil in the Aeneid.

“First of all, in front of everyone, from the top of the rock Laocoön rushes in anger, followed by a large crowd; and from afar: ‘Wretched citizens, what so great folly? Do you think the enemies left? Or do you esteem any gift of the Danaans to be free from deception? Do you know so little of Ulysses? Either the Achaeans are hiding in this wood, or this machine is made to damage our walls, to spy on the houses and surprise the city from above, or it conceals another trap: Trojans, do not believe the horse. Whatever it is, I fear the Danaans even if they bring gifts.’” Publius Virgil Maro, Aeneid, book II, vv 40-50

Similarly, another illustrious presence is that of the Centaur in Greek mythology, a being who was half man and half horse and the protagonist of countless legends.

In Rome, the anatomical and physiognomic depiction of the horse was subsequently perfected: it was no longer just an ideal representation, as a fundamental element of the real dimension of life, but also, and above all, a metaphor of its spirit, strong and that of a conqueror. There are many works in which the figure of the horse is not secondary but an integral part of the narrative, especially in the sculpture that, in a hyper-realist manner, immortalises prancing horses heading for victory on battlefields, with a refinement of working techniques with great ingenuity and sophistication.

The Roman people chose the horse not only as a reference point for everyday, commercial, transport and warfare activities, but also as a faithful ally and, above all, as a symbol of status. It was at this time that a new type of portraiture emerged: emperors increasingly had themselves immortalised in monumental ‘equestrian’ works, capable of imbuing them with an aura of royalty and power, such as that of Marcus Aurelius, formerly in Piazza del Campidoglio and now in the Capitoline Museums.

Having escaped damnatio memoriae, the bronze Equestrian Monument of Marcus Aurelius depicts the philosopher emperor with his beard and wrapped in a toga; he towers over the perfectly harnessed horse, impeccably crafted from the point of view of anatomical mimesis. The Roman monument, considered a purely classical group of statues, led Pope Paul III centuries later, in 1531, to order Michelangelo to find a worthy location in what was the Roman seat of authority par excellence: Piazza del Campidoglio.

What Michelangelo was able to conceive and realise would deserve a separate focus, but we can summarise by saying that he was able to construct, with a Roman sculpture at the centre, the true sense of the Renaissance idea that man is at the centre of the world.

Although this location and the Pope’s request would seem out of place, in truth, Paul III was following a desire that had been carried forward even earlier, since equestrian monuments to great contemporary figures, deserving of political or war exploits and eternalised on their horses in sculptural complexes, were already being erected in the squares of important cities, especially in the north, by, for example, other great masters; Donatello and the Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata in Padua and the Equestrian Monument of Bartolomeo Colleoni by Andrea del Verrocchio in Venice.

With the passage of time, the study of animals also intensified, so that in the Renaissance, their presence in paintings and sculptures was no longer secondary or accessory, but took on a leading role, and some painters became true specialists in this type of work, as in the case of Giovanni da Udine, a member of Raphael‘s workshop. A splendid example of this renewed interest can certainly be seen in the Hall of Horses in Palazzo Te in Mantua by Giulio Romano, one of the most talented and classicist of Sanzio’s workers. In the Mantuan palace, the artist decorated the walls with life-size representations of horses from the Gonzaga stables, making the horse’s role as a status symbol even more evident, so much so that the names of four of the horses depicted are known: Dario, Morel Favorito, Battaglia and Glorioso.

Undoubtedly, one of the most recognisable depictions of the horse’s history in art is its portrayal on the battlefield. Scenes with a multiplicity of elements, which greatly complicated representation, became a fundamental field of study for artists who had to bring back, often for works that praised victories and epic feats, the suggestion of an entire people, a royal house or families of high lineage at the head of cities. It is impossible not to mention Paolo Uccello and the triptych of The Battle of San Romano in which the figures of horses play an essential role in the entire structure of the work, both compositional and emotional, displayed in the Louvre.

Naturally, if we think of horses in battle, we think of Leonardo da Vinci and his numerous sketches of his studies of horses – many of which belong to the Royal Collection of Windsor Castle – aimed, in large part, at the composition of the monumental and, alas, lost The Battle of Anghiari, of which only a mid-16th-century sketch remains, made by one of his followers and reproduced in a very faithful copy by Peter Paul Rubens in 1603.

In the 17th century, this type of subject reappeared, taken up splendidly by Caravaggio who painted The Conversion of St Paul for the Cerasi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome in 1601. Thanks to Merisi, a very important change took place: as in all his painting, the Lombard artist set aside iconographic perfection, blatantly ‘fake’, to give life to realistic and naturalistic paintings, including imperfections. In this work, the horse from which St Paul falls to his death is depicted in its white and brown dappled hide, illuminated by a beam of divine light; its powerful hind legs, front muscles and shod hoof are a grandiose and dramatic allegory of the event narrated.

Over the centuries, the presence of the horse in works of art has changed, as have the customs and habits of society. However, also in the 18th century, as Romanticism was advancing in Europe, Johann Heinrich Füssli proposed a new vision linked to the horse in one of his best-known works, a translation of mystical and oneiric aspects of the night, entitled The Nightmare, and an example of the climate of Gothic nostalgia characteristics of Central European Romanticism. The horse, thus painted, was not inserted by chance: according to Nordic traditions, in fact, nightmares were always heralded by a monstrous dwarf, here visible on the virgin’s belly, a dwarf riding a mare.

The new century opens with a work that has entered the collective imagination: Napoleon crossing the Alps by French neoclassical artist Jacques Louis David. This painting once again entrusted the horse with that lordly role, a noble and powerful ally of the lord that it had had in the imperial era and that Napoleon Bonaparte had revived in an extreme way. In the painting, Napoleon is portrayed as a condottiere, standing tall in his might like the other two illustrious predecessors who crossed the Alps: Charlemagne and Hannibal. In a magniloquent composition, the French general is portrayed at the heels of his Marengo, a trusted companion in yet another heroic undertaking. Heroism that is all-embracing in the entire painting, characterised by Napoleon’s pride and enhanced by the perfection of the horse, white with a thick mane and long tail.

A new social change took place in the 19th and 20th centuries, when the horse became a friend and companion during leisure time, but also a faithful resource for man’s work. Two artists in particular stand out as illustrators of this period: the Frenchman Edgar Degas and the Italian Giovanni Fattori. In the second half of the 19th century, Degas studied the protagonists of the favourite pastime of Parisians in depth: hippodrome racing. He painted several works focusing both on the fascinating anatomical rendering of the horse and on the passionate atmosphere of competition, leisure and tension that prevailed during the races, as can be seen in the painting The Parade announcing a race that was about to take place. As Unika know, the foreground shows the jockeys riding their horses, anxiously awaiting the start of the competition; on the left is the crowd and, in this sort of photograph, Degas captures the scene from an unusual angle, as if he were one of the jockeys. The theatricality that art has shown us up to now is therefore missing; the artist chose, rather, the silence and unawareness of the race experienced by its protagonists: the jockeys and horses.

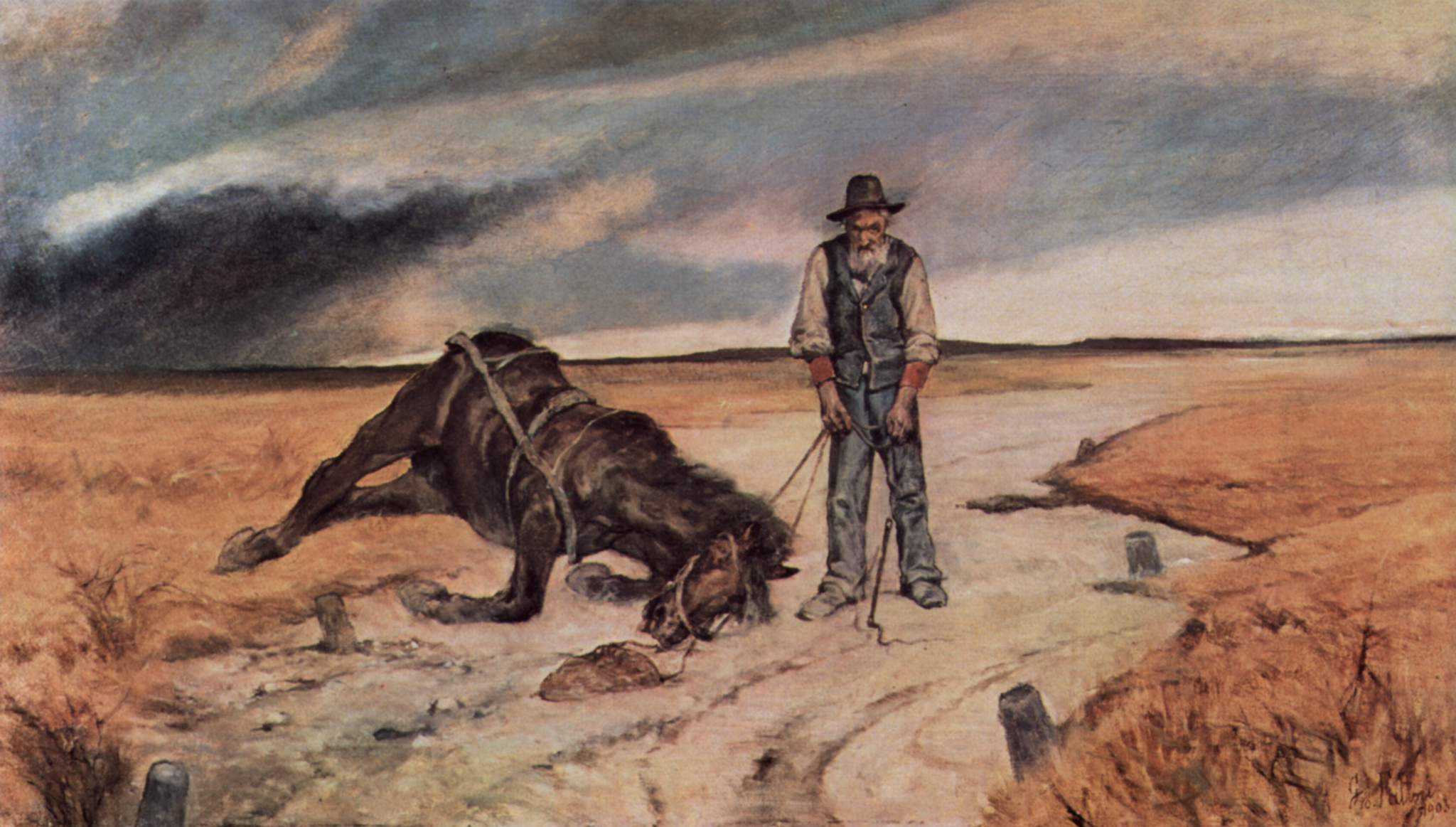

Giovanni Fattori, in Italy, depicted horses in the everyday life of man, with particular attention to the role of the equine as a symbol of work in the fields. A work decidedly rich in pathos and revealing this period is The Dead Horse. In the middle of a wheat field lies a dying horse, exhausted by fatigue and the work of the countryside; at its side a sad and desolate peasant, emblematic of a ruinous loss, in which the bond with the animal is the symbol of one’s livelihood, made uncertain by the sudden death of the horse, a faithful friend but also a precious asset.

At the beginning of the 20th century a period that revolutionised the way we see horses began, in the great upheaval of history. Art responds to change by documenting everything through new languages and styles. In the years between the two centuries, Italy was a source of great and fundamental changes, a period in which the role of the artistic horse also experienced a moment of renewed interest, in particular, thanks to the impulse offered by artists and currents of the century that had just begun: the energetic and radiant Futurism and the static and mythological Metaphysics.

We will cite two examples as follows: Umberto Boccioni depicted the horse as an impetuous element of dynamism in his Futurist canvases, as shown in one of his earliest works from 1910, The City Rises. Painted while contemplating work on a construction site in Milan, the horse stands in the centre of the painting and is a clear symbolic reference to the evolution, productivity and acceleration advocated in Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto. The horse is taken by Boccioni as a reference of untameable fury, thrashing about unable to be appeased. Society, says Boccioni, changes, evolves, progresses towards the future and cannot stop, while humanity can only adapt to this evolution.

The second Italian artist named is Giorgio De Chirico, who took up the horse, unlike Boccioni, placing it in different scenarios, such as coastal expanses, in a placid and indefinite time, an unknown space that was lost in a reference to classical civilisations. In the work Horses by the Sea – a subject the metaphysical painter took up several times – the two animals are portrayed in their mythological majesty, slender and defined by vigorous brushstrokes and sculptural chiaroscuro. Described in this manner, they appear as an allegory of human feeling, suspended in an inexplicable limbo.

In Germany, France and Spain, the change was implemented in other languages and the figure of the horse continued to interest artists. We will highlight Franz Marc in Germany, who took up the equine subject in order to break it down, recompose it and make it an element of complex pictorial experimentation that in the space of a few years presented very evident differences. Marc was also one of the exponents of a movement of artists formed in Munich that was active from 1911 to 1914, until it was dispersed by World War I. The name of the movement speaks for itself: Der Blaue Reiter, or ‘The Blue Rider‘.

The power of experimentalism reached Spain and, in the hands of Pablo Picasso, was transformed to the point of giving the horse a key role in the work denouncing Guernica, painted in 1937 following the aerial bombardment of the Spanish city during the civil war. In this case, the horse becomes the symbol of an entire people. The desperate torment that animates the entire work focuses at its centre on a wild and frightened animal representing the Spanish people, exhausted, disturbed and alienated by the civil war.

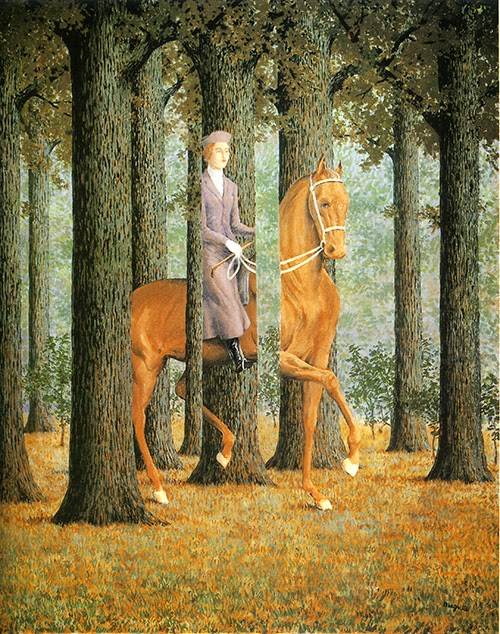

This brings us to France, where René Magritte transformed the horse into a surrealist subject in The Blank Signature. In the work, a lady on horseback in the woods among many tree trunks becomes the subject of a series of volumetric games and perspective decompositions in which she and the horse appear and disappear, an emblem of a furtive gaze on life. Magritte wanted to demonstrate a rather simple concept in a surreal way: in everyday life there are things that you can see at certain times and at others you cannot; however, this does not mean that at the moment you do not see them, they do not exist.

This survey that Unika wanted to do on the portrayal of the horse in art is not yet finished and in the coming months, we will show you how contemporary art has chosen to depict our beloved horses…

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

If you have ever walked through the stables or along…

Colic is one of the most common and delicate issues in horse care.

Thanks to its anti-inflammatory, anti-oedemigenous and pain-relieving properties, it is perfect for protecting horses’ osteoarticular well-being.

The use of clay dates back to very ancient times and even today it has not lost its fame as a natural remedy with a thousand uses.

The warm season is upon us and for many riders it is time to take the clipper in hand…

Here we are at our second meeting with our Unika Blog Naturopathy section. I am Sara Maiani, specialized in Natural Medicine, Clinical Phytotherapy and Naturopathy.